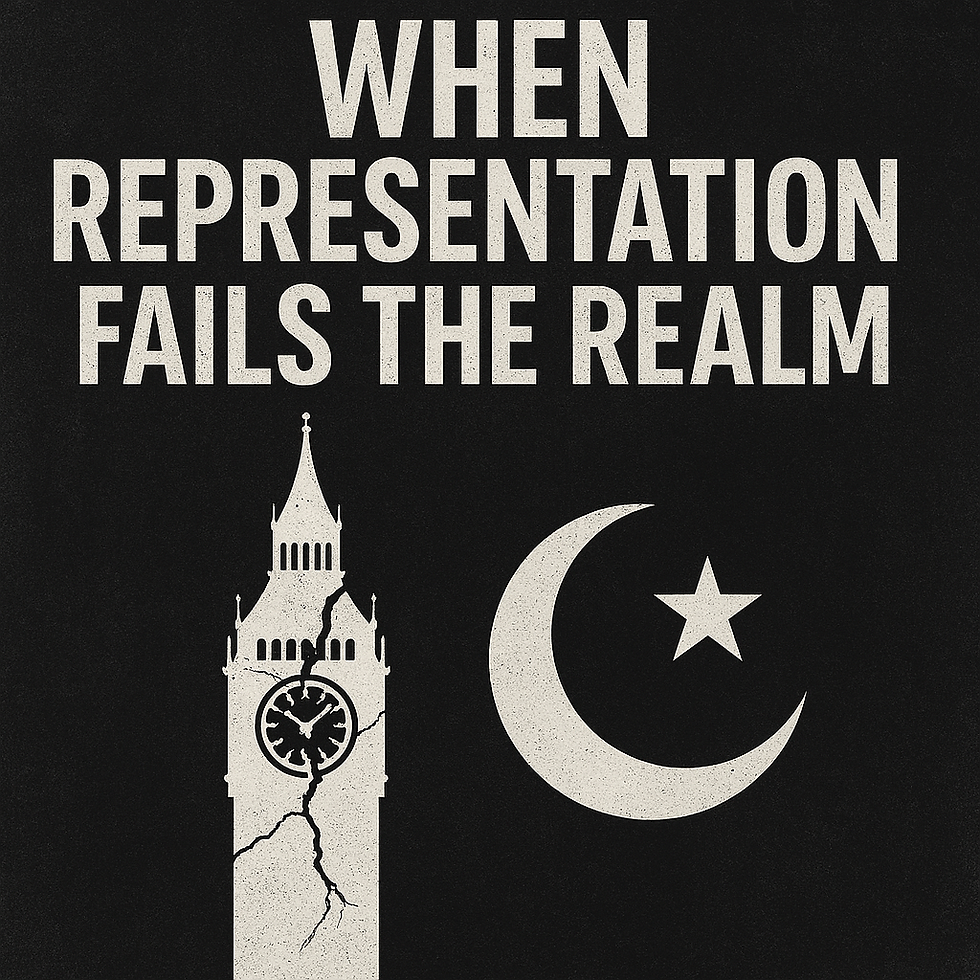

When Representation Fails the Realm: Language, Loyalty, and the Limits of Multicultural Democracy

- Whispering Quill

- Aug 24, 2025

- 3 min read

By Daren Norman

The United Kingdom’s democratic machinery rests on a deceptively simple premise: those elected to Parliament or local office must be able to scrutinise, debate, and legislate in the language of the law — English. This is not cultural chauvinism. It is the bedrock of constitutional accountability.

Yet in recent years, a quiet but profound shift has taken place. In constituencies with large, tightly organised Islamic communities, candidates have been selected — and in some cases elected — who cannot engage fluently in English. They rely instead on community intermediaries, religious institutions, and bloc voting to secure office.

This is not representation. It is delegated power without direct accountability.

The Constitutional Breach

Parliamentary debate, statutory interpretation, and committee scrutiny are conducted in English. An elected official who cannot follow or contribute meaningfully to these processes is constitutionally incapacitated from day one.

In practice, this means:

They cannot interrogate ministers or civil servants without translation.

They cannot draft or amend legislation themselves.

They cannot engage with the national press or the wider electorate without mediation.

The result is a democratic blind spot — a seat in the chamber occupied, but not functionally active in the national conversation.

The Ideological Vacuum

Nature abhors a vacuum, and politics is no exception. Where linguistic and civic competence are absent, ideological frameworks step in. In some cases, these are explicitly religious — rooted in Islamic jurisprudence and community priorities rather than the secular, pluralist principles of the UK’s constitutional order.

This is not conjecture. Across certain local authorities, we have already seen:

Policy capture on issues such as faith‑based schooling, gender segregation at public events, and the accommodation of Sharia‑influenced arbitration in family disputes.

Electoral mobilisation driven by religious identity rather than policy platforms, as evidenced by coordinated campaigns like The Muslim Vote in the 2024 general election.

Parallel governance structures within communities, where mosque committees and religious councils wield more day‑to‑day influence than elected councillors.

The Stealth Mechanism

This is not an overt coup. It is incremental institutional capture — a “caliphate by stealth” in which the levers of democratic legitimacy are used to advance a worldview that is, at its core, incompatible with the secular rule of law.

The mechanism is simple:

Demographic concentration in specific wards and constituencies.

Candidate selection based on religious affiliation and loyalty to community power‑brokers.

Bloc voting that delivers safe seats without the need to appeal to the wider electorate.

Policy influence exercised locally, then scaled nationally through party leverage.

The Lebanon Lesson

Lebanon’s descent from a Christian‑majority, pluralist state into a Muslim‑majority, sectarian‑captured state was not an accident. It was the product of demographic shifts, refugee influxes, and the embedding of armed ideological actors within the political system.

The UK is not Lebanon — yet. But the structural vulnerabilities are eerily familiar:

A political class unwilling to enforce civic integration standards for fear of being branded racist.

Electoral systems that reward concentrated identity blocs.

A media ecosystem that treats “diversity” as an unqualified good, even when it masks sectarian entrenchment.

The Red Lines

If the UK wishes to preserve a functioning, secular state, certain principles must be non‑negotiable:

Mandatory English fluency for all candidates seeking public office.

Oath of constitutional loyalty that explicitly affirms the supremacy of UK law over any religious code.

Transparent candidate vetting to ensure no undeclared allegiance to foreign or religious authorities.

Reform of electoral law to prevent bloc‑vote capture from undermining pluralist representation.

Conclusion

This is not about Islamophobia. It is about constitutional hygiene. A democracy that cannot guarantee its representatives can speak the language of its laws, defend its secular framework, and represent all constituents equally is a democracy in name only.

The UK must decide — and soon — whether it will confront this creeping dysfunction, or whether it will, like Lebanon, wake up one day to find that the state it thought it had is gone, replaced by something far less accountable, and far less free.

Comments